What is a Sanction?

In this blog post, we’ll be discussing what sanctions are, how to operate your company with your sanctions knowledge, and what the international environment is like in 2025 regarding sanctions.

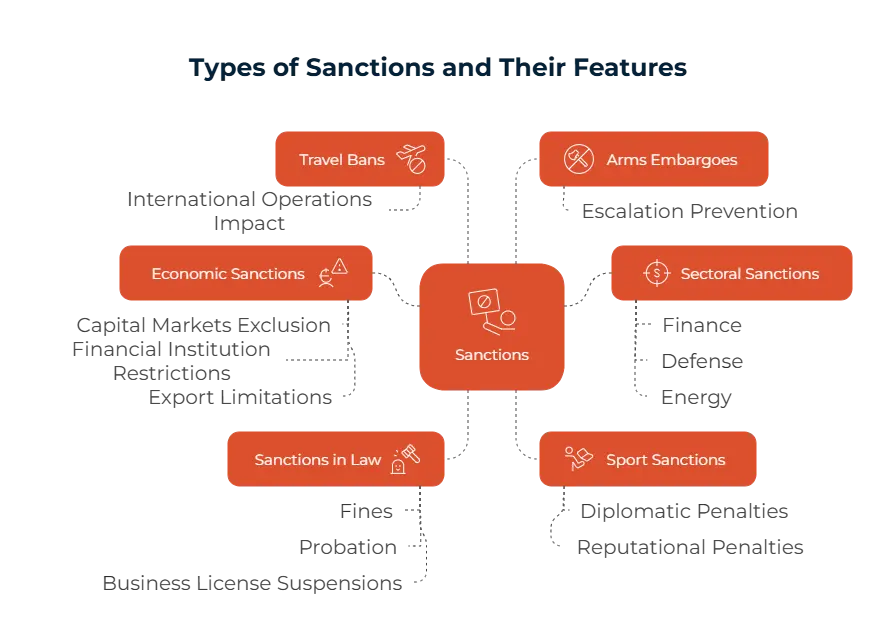

Sanctions are a form of punishment that is decided by governments or internationally operating regulatory bodies to restrict relationships of any kind with people, companies, or countries that are risky to do so. Recently, Trump’s meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy affected the EU sanctions; around 70% of the new sanctions were directed at Russia, upping the economic pressure.

How Do Sanctions Work?

There are several ways to implement sanctions. One way is using watchlists to first identify these sanctioned parties; some examples to these are the U.S. OFAC SDN List or the the EU’s Consolidated List. Banks and similar other firms are required to screen against these lists and then allow these people and companies to complete transactions. Another way you can use sanctions is banking restrictions, some of these are cutting the said company off from global payment networks like SWIFT, freezing their assets, and prohibiting partnerships between them and other financial firms. This way, it is much harder for them to move money or have any international credit. On an individual level, travel bans where sanctioned people can’t cross borders or enter certain areas is also encouraged.

Export controls is another way that is used; governments can limit or completely ban selling of certain goods, services, and technologies to sanctioned parties. This is mainly done for items that can be used for military or other illicit purposes.

Purpose of Sanctions

These sanctions help create a safer global environment in many ways. Punitive sanctions are done after violations, like North Korea with their nuclear program and illicit weapons development. Preventive sanctions are tasked with stopping the conflict before it even started, like arms ebargoes that stop the sale of weapons into unstable jurisdictions. Sanctions can also be coercive; these aim to lead the country or firm towards a more compliant approach. One example to this is pressuring a state to get out of an illegally occupied terrority to stop them, Russia and Ukraine war can be a case where this is seen.

Who Imposes Sanctions? Key Regulators

Sanctions are decided by different regulatory bodies around the world. The United Nations has a global role in setting and implementing sanctions that then the member countries follow. In Europe, the European Union has the most say with its own sanctions to ensure regional stability within the continent. Another important player, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) operates in the U.S. This regulatory body influences the global transactions since the U.S. dollar is dominant worldwide. In the UK, the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) is known for their sanctions compliance works.

What Is a Sanction Check?

A sanction check is conducted by screening people, companies, and other entities against the sanctions lists we’ve mentioned above to make sure your company is compliant with Know Your Customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) regulations. Ensuring sanctions screening compliance helps you also by completing a part of customer due diligence procedures. These checks are especially important for international transactions where you need to ensure compliance with both countries.

Impact of Sanctions

There are several consequences of getting sanctioned. The first we’ll mention is supply chain disruption; the trade bans and export controls affect the availability of goods. Another impact may be restricted financial access for sanctioned countries and firms. These entities may lose their access to banking systems, international transactions, and credit markets. With these results building up, it may lead to higher inflation and rising poverty rates. We can give Russia as an example, the recent sanctions have caused Russia to increase its production costs.

Embargo vs Sanction: Key Differences

These two terms have different meanings and we’d like to clarify further for our readers. A sanction is targeted to a specific individual, company, or sector; it focuses mostly on financial or trade restrictions. One example we can give is the OFAC SDN list which helps prevent sanctioned parties from partaking in the U.S. financial systems. On the other hand, an embargo takes a broader approach, and it involves a full ban on trade or economic activity that affects an entire country. The U.S. embargo on Cuba can be given as an example; this embargo restricts almost all commercial interactions that is done with the country.

| Criteria | Embargo | Sanction |

| Definition | Trade ban | Penalty / restriction |

| Scope | Goods & services | Person, entity, country |

| Purpose | Economic pressure | Political/financial punishment |

| Application | Import/export block | Asset freeze, travel ban |

| Duration | Long-term | Flexible |

| Example | U.S. embargo on Cuba | OFAC sanctions on Iran |

Embargo vs Sanction: Real-World Examples

We’ll give you some examples from different countries to help further clarify the difference. In Russia, there are sanctions from the U.S., the EU, and UK, but there is no full embargo. Iran faces both targeted sanctions and a broad embargo enforced by OFAC and the UN. According to the CNN, as of August 2025, Iran faces a renewal of UN-mandated sanctions within weeks unless it returns to negotiations on the future of its nuclear program and allows international inspections of its facilities.

North Korea is under the same situation, the sanctions and embargoes are coming from both the U.S. and the UN. Syria deals with sanctions and partial trade restrictions as embargo, coming from the U.S. The EU dropped its economic sanctions in May, 2025 to support the Syrian people. Cuba is also both subject to embargoes and sanctions from OFAC.

How Sanctions Affect Compliance

Key Compliance Needs

Your company should implement some crucial features to make sure they are reaching compliance. The first item we at Sanction Scanner recommend is KYC and KYB screening to ensure no sanctioned party can interact with you. AML transaction monitoring, export control checks, and supply chain audits are needed to check the data against suspicious activities and catch them as soon as possible. Filing Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs) or Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) is what a responsible company should do when faced with odd activity.

Common Penalties

Common instances you should watch out for will help you in the process of compliance. The first is not screening against updated sanctions lists. This action can lead to severe fines. Another example is bypassing sanctions through third parties, which is extreme and should be avoided. Finally, serving embargoed countries without the proper licenses will also cost your company a lot, both financially and reputation-wise.

Compliance Guide: Sanctions Checklist

We will now walk you through what an ideal company does to ensure sanctions compliance. You should first find out which regulatory bodies are the most prominent in your jurisdictions, like OFAC, UN, or sanctions. After this, you should figure out a stable sanctions policy with outlines. Your next step should be to screen your clients and also keep your sanctions lists updated during this process to make sure you miss no sanctioned party. Training your staff accordingly is also important when you’re looking to reach compliance. Reporting any suspicious findings you have will also help you stay compliant. Our final advice and step is auditing your systems and controls regularly to ensure your program is working like it should.

Detection & Prevention: Sanction Scanner

Our experts at Sanction Scanner offer our tool for detecting and preventing sanctions lists related crimes to our readers. Our team’s real time sanction list screening is great for finding sanctioned parties. The ongoing monitoring feature coupled up with PEP screening also offered by us the sure way to go when you’re looking to protect your company against crimes. Our adverse media screening feature will also ensure your customers flagged against reputational risks that may be caused by negative news.

FAQ's Blog Post

U.S. sanctions apply to non-U.S. companies if they use U.S. dollars, tech, or business ties.

Yes, individuals can be sanctioned for terrorism, corruption, or human rights violations.

Yes, even indirect dealings can result in penalties, especially under U.S. or EU law.

Yes, OFAC and EU regularly sanction crypto wallets linked to illicit activity.

Yes, banks are required to freeze assets if the account holder is on a sanctions list.

No, UN sanctions must be adopted into local law to take effect.

Yes, strict liability often applies, even without intent, unless proper screening is in place.